Articles

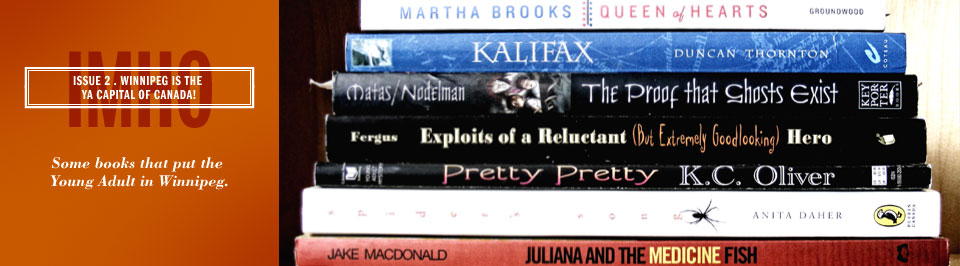

Winnipeg, Heart of the Continent and Teen Lit

By Anita Daher (originally published Feb. 28/2011)

Whether the seeds of creativity that would one day become Winnipeg’s Young Adult writing community originated in primordial bacteria, MORE >

Prize Culture: You're Next!

By Shane Neilson

The next poetry contest in Canada is coming! It’s a contest that competes… with other contests. It takes all the winners of the other contests conducted in a calendar year and decides upon one winner MORE >

Poll: Which books should our fearless leaders read?

Interviews

‘Modern Canadian Poets’: An Interview with the Editors

Kids Actually Read: An Interview with Jake MacDonald

Jake MacDonald is a Winnipeg writer probably best-known for his successful career as a print journalist MORE >

Jake MacDonald is a Winnipeg writer probably best-known for his successful career as a print journalist MORE >

New Work

Winnipeg through Gord Arthur’s Vintage Polaroid

by Ryan McBride

The object in the hands of Winnipeg photographer Gord Arthur looks innocent enough at first: a flat, buff-coloured brick MORE >

Puppet: an Earthquake Memoir by Toshiro Saito

Translation and Introduction by Sally Ito

On Friday, March 11, 2011 a severe earthquake followed by a massive tsunami hit Japan, destroying vast areas of northern Japan and claiming thousands of lives. MORE >

Excerpts

Attempting Archaeology

By Struan Sinclair

‘So I’m right into your old lady,’ Murray says. He palms his phone, flicks his fingers over its illuminated keypad. ‘It was an accident waiting to happen.’ MORE >

Book Reviews

-

‘Irma Voth’ by Miriam Toews

Reviewed by Michelle Berry (originally posted April 5, 2011)

Reviewed by Michelle Berry (originally posted April 5, 2011)Irma Voth, Irma Voth. I don’t know what to make of you.You are: novel-screenplay-movie-painting-photograph.

You contain: tragedy-comedy-subtlety-boldness- aggressiveness- guilt- extravagance- outrageousness -courageousness. MORE >

-

‘Bloodlands’ by Timothy Snyder

On March 16th of this year, hundreds of relatives and surviving veterans of the Latvian Legion, a formation of the Waffen-SS created by the Germans in 1943 and part of one of the last armies still fighting in Eastern Europe during World War Two, staged their annual march in central Riga to the famous Freedom Monument, MORE >

-

‘No Safe Place’ by Deborah Ellis

Deborah Ellis starts her new novel, No Safe Place, in the middle of the action, no “Hi, I’m so and so.” MORE >

-

‘The Blue Light Project’ by Timothy Taylor

Everyone was adrift. The encircling authorities, the cameras, the grip of the hostage drama itself. Everyone was living in fear about the end.The ending was the thing. And Loftin felt it in a flash, his own story arriving. There was a great war going on here about control over the ending. Each breath of this common air fully vested. MORE >

-

‘The Door to Lost Pages’ by Claude Lalumière

In the world of Claude Lalumière’s The Door to Lost Pages, history and myth are treated as one whole. But that should not feel so strange—think of the ancient city of Troy; you cannot discuss its truth divorced from the legend. For the reader willing to step into Lalumière’s fictional bookshop, Lost Pages, whole new worlds become accessible. MORE >

Editor’s Rant #2

By Maurice Mierau

Book culture in this country is, on a good day, adolescent. By which I mean self-absorbed, badly-informed, and lacking in hygiene and urbanity. Since Canadian literature began around 1960, that means our book culture is a fifty-year-old teenager, living in his parents’ basement. Not good, and in need of some critical house-cleaning, which I’ll get to. So we—Canadian literati— are Young Adult in a sense perhaps not intended by the authors of the books whose spines decorate our issue 2 home page; but in the Middle East right now the population’s huge swath of young adults is re-defining the meaning of adolescence. I sit down to write this as many young citizens of Tripoli once again risk their lives for the sake of democracy and freedom. They use the same gadgets many Canadians do—checking the Facebook pages of their hundreds of intimate friends. And then they connect in a way I certainly would not have the courage for, in the face of large-caliber automatic weapons fired by people with nothing to lose.

Early in 2009 I had the great pleasure of meeting the Canadian poet P.K. Page in her Victoria living room. It was the cocktail hour, and Page, who was then 92, downed two cocktails with visible enjoyment while she showed a remarkable curiosity and verbal lucidity. When I started ranting about politics, she asked if I was “a political poet.” I said no, I’m just a poet who happens to be interested in politics.

The same could be said about the editorial interests of The Winnipeg Review. We’re a literary magazine that happens to be interested in politics and culture. As editor, I go out of my way to find writers who, while they might not risk their lives at a demonstration, at least have the courage to speak clearly about how literature and books really matter.

Book reviewing in this country still features far too many writers reviewing each other as favours in some postmodern cargo cult, and by an ongoing chilly climate towards real criticism that grows too many puff pieces disguised as reviews. These kinds of pieces have some minor informational value, but they also intensify my feeling that CanLit is still a regional high school dominated by a few powerful cliques who drive cool cars and wear fashions that were big in New York five or more years ago. The books that get reviewed by the authors’ friends are not necessarily bad, it’s just that these reviews add an unpleasant smell of nepotism to the atmosphere while blurring the line between criticism and promotion.

You could argue that the literary scenes in New York and London are really just bigger high schools where the nepotism is not as immediately noticeable because of the bigger student body, and I would have to agree. There was never anything mature about Norman Mailer. I don’t want to suggest that we will ever get out of high school, but rather advocate for a bigger high school, more cliques, more open conflict, and less slavish aping of fashions from the really big high schools in other countries.

What is real criticism anyway? I know it’s not fashionable but I still believe in some version of critical objectivity. Of course when you write criticism you are influenced by all kinds of subjective factors: your own background, your reading experience, who you studied with, seeing or hearing the author read, what they looked or sounded like, how the book is designed, what the quality of the paper is, what you just ate and drank for dinner, etc. As a professional reader though —and that’s what a book reviewer really is — you do have a responsibility to read professionally. I think that means you must account as objectively as possible for the subjective experience of reading.

Then there is our literary culture’s sequacious avant gardening. Just because we live in a chronically insecure culture doesn’t mean we have to recycle other people’s aesthetic experiments. There is nothing more provincial than adopting somebody else’s now-wrinkled innovations. Making it new always means recombining various things that already exist, and it takes writers aware of the larger literary context, in Canada and beyond, to recognize what is truly new.

Perhaps what I want is the impossible ideal articulated by Bubbles on The Trailer Park Boys, where he metaphorically suggests stealing just a little pepperoni at a time rather than going for the whole refrigerator-full. Like Bubbles, I want crime in moderation, subjective objectivity, worldly innocence. Worldliness has to be carried lightly. A truly sophisticated review impresses, charms, and ultimately influences, simply by giving an honest account of reading a book.

As editor, my hope is to bring you reviews that are honest accountings not only of Canadian fiction but of the larger culture, all as part of TWR’s issue 2. Over the next seven or eight weeks you’ll see reviews of Miriam Toews’s new novel, the Swift and Jones anthology Modern Canadian Poets, the nonfiction tour de force of Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands, and more discussion and reviews of YA literature. And of course you’ll get generous helpings of our columnists, and new work by gifted poets and fiction writers. For those of you who missed TWR issue 1, you can read it all here in our past issues area, complete with the original banner.